WE ARE a people of dates, commemorations, celebrations and anniversaries. Be it the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 or the Battle of the Bogside in 1969, most of us can rhyme off a long list of momentous dates. Yet only those of us old enough to have lived through the Troubles can fully appreciate the magnitude of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement on April 10 1998.

I was 37 when it was signed, which means I’d known nothing but the conflict. Like most people, I was glued to local news for most of that day and when success in the negotiations was announced, I went to bed, stunned. Could it really be possible that, for the first time in my life, I might waken to a peace I’d never known?

But while that was a wonderful day, I also sadly remember a multitude of other days during those 37 years I’d much rather forget.

At age 10, I was standing in my grandmother’s garden in the Sperrins, when news filtered through of Bloody Sunday in Derry. As a teenager I remember listening, horrified, to the radio as reports of the La Mon House bombing broke. Much later, I was driving through Belfast on a sunny Saturday afternoon, when I heard so many sirens it sounded like the city itself was screaming; it was the day of the Shankill bombing.

And just when I’d begun to believe peace might finally be a reality, I found myself sitting in a B&B in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, where I was performing in a comedy club, watching the horror of the Omagh bombing unfurl on the small television in my room.

For those of us who survived that horrific time, death and destruction, like the sound of helicopters overhead, had become so commonplace they were no longer noticed. We had become inured to the madness which surrounded us, with even those in authority using the term ‘an acceptable level of violence’.

As a society we hadn’t become so callous that we couldn’t empathise with victims or their families but, to maintain our sanity, we adopted a detachment similar to those working in the emergency services. The only exception was when someone you knew personally became a victim. I will always remember two school friends who were killed simply because they were the wrong religion, in the wrong place, at the wrong time. On such vagaries balanced whether you lived or died. I know but for luck, I could have lost my life on at least three occasions.

So while I’m often critical of our political class it’s important to remember that, for a brief moment, a group of local politicians put not only their reputations, but also their very lives, on the line for peace. Historic enemies sat round a table and made compromises and accommodations most thought impossible. And when the agreement was put to a vote, knowing it meant prisoner releases, thousands of people bravely put their grief and loss to one side to vote for a better future.

That 20-year-olds today only know of this time through history lessons or television documentaries is testament to the miraculous transformation brought about by the agreement. While our present political difficulties are both disappointing and frustrating, no blood has been spilt and there are no threats of violence – for that we owe gratitude to those who worked into the small hours of that April night in 1998.

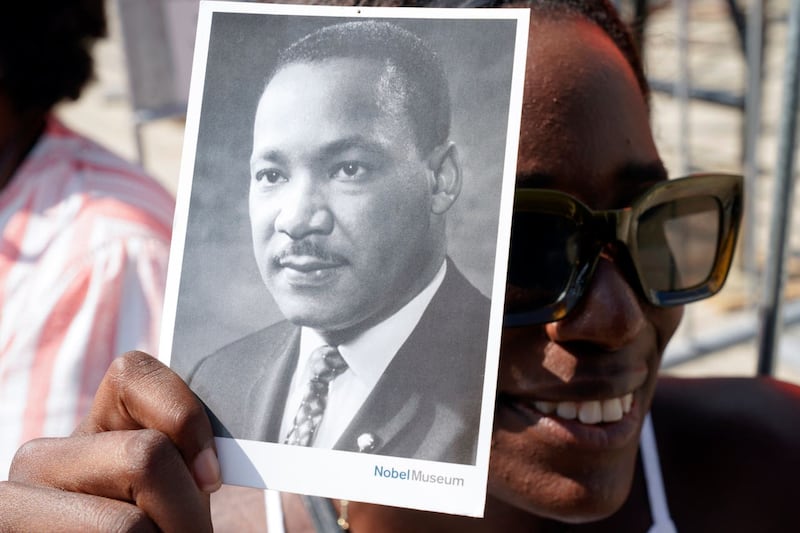

While all involved are to be admired, two figures deserve special mention. It is no exaggeration to say that without the dogged determination of John Hume, and the charisma of Mo Mowlam, there would be no peace. That the Sunday Business Post Magazine last week omitted both from a front page picture featuring the main players in the agreement was unfortunate.

I bitterly regret not following my instincts when, in London in 2001, I was walking back to my hotel after a gig when I noticed Mo Mowlam standing with her partner in a restaurant. I wanted to go and thank her for all her efforts but decided not to impose on her privacy.

I didn’t make the same mistake a few years later when I performed at an SDLP dinner. At the end of my set, I thanked the audience but said that would my first and last appearance, explaining I’d accepted their invitation for one reason – so I could express my admiration for John Hume, who was in attendance. His and Mo Mowlam's efforts for peace should never be forgotten.