IN A (professional) lifetime spent in and out of prisons, visits to Maghaberry and the Maze were among the strangest I made.

The governor, the late Duncan McLaughlin, took me around Maghaberry. Normally I wasn’t expected to give prisoners my name, but Maghaberry had its own protocols. My name and purpose were demanded, courteously enough, by the woman to whom we made a beeline in the first workshop. She quizzed me intently then, apparently satisfied, delivered a fluent and evidently well-practised denunciation of the British government’s treatment of prisoners. Only then was I allowed to go on.

As I approached other women around the prison the governor nipped in quickly to confirm that I had already been spoken to by X – who, I later learned, was the IRA’s Maghaberry OC.

At the decommissioned Maze a few years later there was a chance meeting in what had been the offices of the prison’s senior administrators. Two men were leaning over a meticulously detailed scale model of the prison. (Where is it now, I wonder?) They were deep in reminisces about events past, when this had been their abode.

They recalled the protests about prison food, so bad that they had agreed to throw it away. As a counter to the waste, food parcels (their fallback) had been stopped. A trading and mutual aid system between the compounds (operated by overhead pullies) was the prisoners’ counter move. One of the pair recalled the hooch (prison alcohol) that had come from the other’s compound in exchange for bread: excellent quality.

I later learnt that one this friendly pair had served time for serious loyalist offences, the other for republican ones; literally deadly enemies. Their affable chatting conveyed no hint of this.

This is the type of frequently surprising turn and twist that shaped my trilogy on Irish political prisoners, the final volume of which has just been published by Routledge.

From the outset I knew I needed to go beyond the thousands of records and documents we had to trawl. The intent was to describe the human dimensions of extraordinary times and places.

There was indeed an intensive examination of Irish and British archives, public and private records, memoirs and diaries and the like. But the book had to be given further depth through a range of interviews and conversations. Former internees and prisoners of all hues, families, staff, clergy, officials and politicians, those who had been tortured, as well as victims and survivors of paramilitaries, all spoke to us.

Most retained deeply unpleasant memories – vivid and apt to surface at any time. There was the administrator who always looked for a radiator when he entered the H-Block wings. He knew he would be mobbed. Dreading it, he did not want to be seen to tremble and leaned against the chosen radiator.

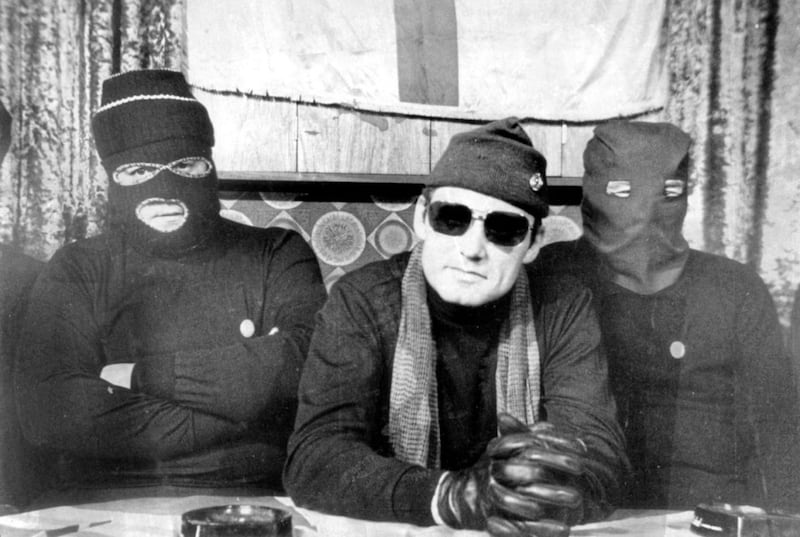

A victim of torture – one of the ‘hooded men’ – was convinced that he would be killed to prevent him from talking should he be released; he wanted them to get on and end it. And there was the ceaseless struggle between the authorities and the prisoners for control. On the tactics, "The republicans wrote the book," Gusty Spence, the loyalist leader, told me.

There was a quarter century of exposés from the campaigning priests, Fathers Denis Faul and Raymond Murray, as well as interventions from Cardinals Conway, Ó Fiaich and Daly. Clergy of other denominations vented their own pastoral and representational concerns, each in his own way. Officials planned carefully for these meetings.

And at the end, the assent of the prisoners of both sides was necessary for the Good Friday Agreement to proceed. It was in character when Mo Mowlam disregarded her officials’ advice, went into the prison, and sat down with some of the most violent prisoners of those awful years. She asked for and got their support.

The earlier volumes (1848-1922) and (1920-1962) examine other parts of the tapestry’s 150 years: characters, places, happenings, triumphs, tragedies, well-laid plans and unforeseen consequences fairly tumble off the pages.

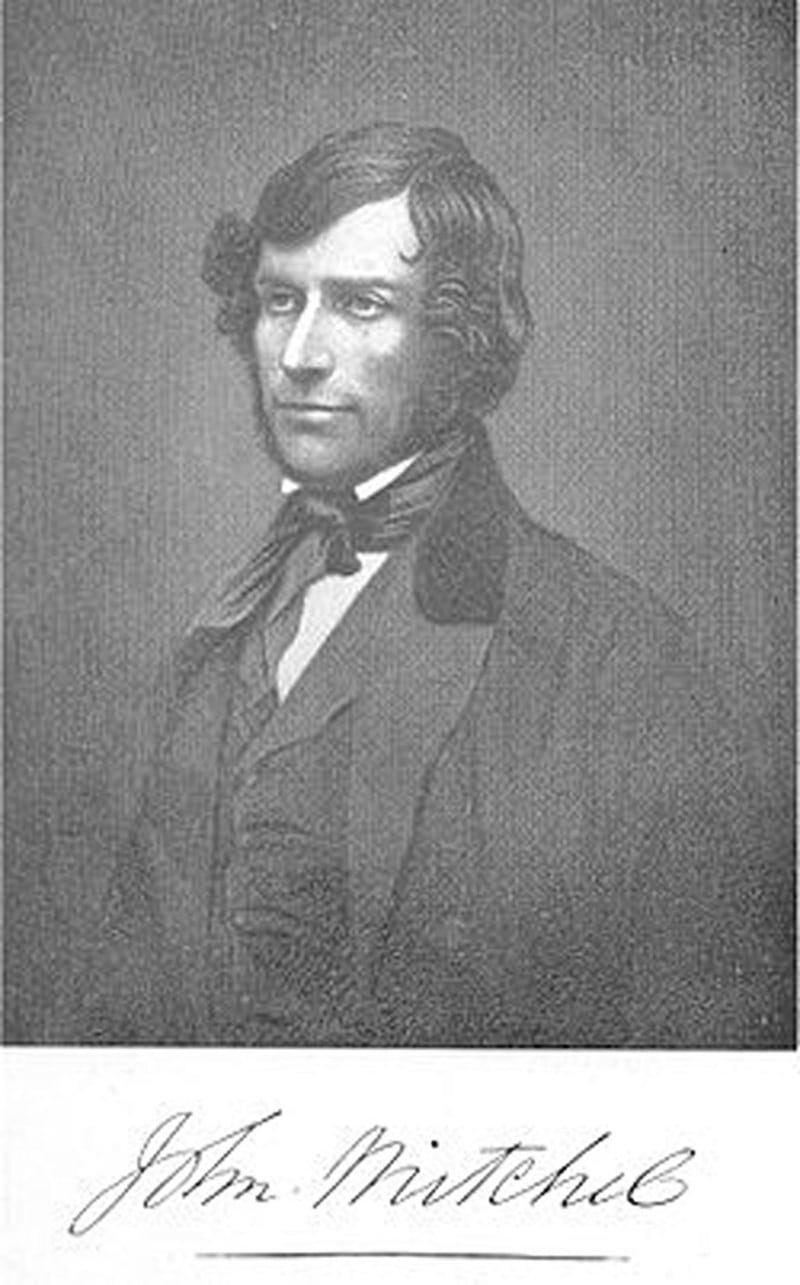

The tale begins with a paradox. Worried about popular reactions, Dublin Castle wanted to preserve the life of a certain Newry solicitor turned amateur insurrectionist, John Mitchel. Were he charged he would almost certainly have been found guilty of treason and hanged. Tailor-made legislation (the Treason Felony Act, 1848) provided a less inflammatory solution.

Banished instead to the far side of the globe, Mitchel, with the other Young Ireland leaders, never ceased to be bothersome, locally and internationally; they just had to be to be felt. Here was authority’s still insoluble conundrum: arrests seem fine, but political prisoners can turn their punishment into an instrument of a wholly different kind.

Yet the Fenians of the 1860s served hard time in convict prisons until Gladstone’s Damascene moment revealed his life’s mission: seeking justice and peace for Ireland.

The dynamitards wanted none of it and fantasised that Nobel’s useful new explosives (and a proto-type submarine) would bring down the British Empire. It did not turn out well for many and they also served long and even harder sentences, largely forgotten, sometimes repudiated.

Imprisonment shaped events for another generation when in 1916, Frongoch (a makeshift internment camp set around a disused north Wales whisky distillery) became a college of insurrection, with a distinguished roll of old boys, including Michael Collins.

Civil war attended the painful birth of the Free State. Only recently vacated, gaols and camps had a new intake, and some bemused staff guarded cell doors that a few months before they had themselves sat behind.

Sixteen years on, the Second World War threatened to overwhelm the neutral southern state and the de Valera government, seized with fear-infused fury, acted to defend it. There were hangings, shootings and long sentences and the Curragh Camp – ‘Tintown’ – opened for business. Boredom and hopelessness sucked its residents into their own civil war.

Factions blossomed and fed whirlpools of slights given and taken, denunciations, expulsions, and elaborately sadistic shunning ceremonies. Release came, but grudges were inexpungible.

It seemed that armed republicanism had consumed itself, as in a sense it had. The 1956-62 Border Campaign was a type of afterthought – an exercise detached from reality, careless of lives and property. Internment was revived north and south, and again some received long prison sentences. Few cared when they eventually returned home, one bitterly recalling that his neighbour welcomed him back from "working in England".

Irish Political Prisoners 1960-2000: Braiding Fury and Sorrow by Séan McConville is published by Routledge in hardback and e-editions. Irish Political Prisoners 1848-1922: Theatres of War and Irish Political Prisoners 1920-1962: Pilgrimage of Desolation are also available from Routledge (paperback and e-versions).