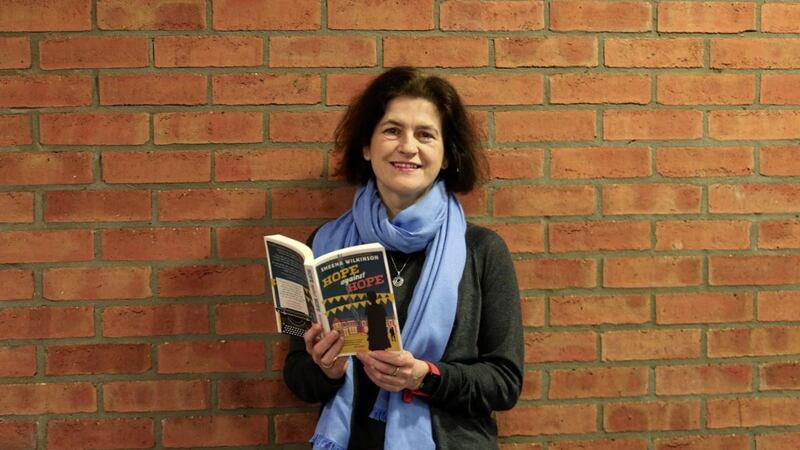

THE Irish border is not, on the face of it, a "sexy" subject says Sheena Wilkinson of her new 'coming-of-age' novel set in Belfast in 1921, but even she could not have foretold how relevant it would become for 2020.

"I did write the book deliberately against the backdrop of Brexit and because we are approaching the centenary of Northern Ireland – I'm not pretending I didn't – but I don't think I could have predicted, when I was writing it, just how significant the border issue would become again, with new talk of a border poll," says the award-winning Co Down author whose latest offering, Hope against Hope, is out on Thursday.

It is the third in a series of historical novels penned by the former teacher (and sometime folk singer) and takes a look at the complicated lives of young women from across the social as well as religious divide who arrive at cross-community hostel Helen's Hope, whose "progressive, feminist space" is viewed with suspicion in a fractured, post-Second World War Belfast.

The young heroine, Polly, is a Catholic girl from fictional border town Mullankeen who arrives at the hostel after she is attacked by her alcoholic brother, himself traumatised by experiences as a soldier in the First World War.

A stand-alone novel aimed primarily at young adult readers, it follows Name Upon Name (2015), a story based around the Easter Rising from a northern perspective, and the hugely successful Star by Star, published in 2017 and set against the 1918 general election when women in Ireland voted for the first time. All three books have celebrated young women coming of age against a background of political turmoil – which is exactly what the Castlewellan writer, now aged 51, did herself.

"I grew up with the border a physical, frightening thing and my own background is mixed, so I always remember feeling a certain amount of confusion," Wilkinson says. "This was largely because I was always surrounded by people who were so certain of their place in Ireland, their place in Northern Ireland, their place in Britain...

"I didn't have that certainty but later I came to see that as a very positive thing because I could take what I wanted, I suppose, from both traditions. Now, I'm a proud and active member of the Alliance Party and, as someone really interested in women's stories and feminist history, it was important for me to have a girls' hostel that was religiously mixed.

"In the early 20th century, many women came to big cities to work and there were lots of hostels for them – they were an actual thing – but the one in my book is unusual because it's set up as a cross-community space by women who are quite politically engaged. There is no evidence for such a hostel existing, but there were some forward-thinking people around that time who were starting to think of alternative ways of living. It's very much a social experiment but, unfortunately, not everyone shares its values..."

Wilkinson likes to do her research and has woven in real-life events – a shooting following a Glentoran football match actually happened and she references a film, Dream Street, which was showing in Belfast picture houses on the date and year mentioned in the book. And alongside the central storyline there are often topical sub-themes skulking in the background: In Hope against Hope, these include an inferred but not stated lesbian relationship and exploration of the treatment of nationalist soldiers returning from the front.

"As someone from a mixed background, I feel passionately about this and I think we've been very slow to acknowledge the full extent of Ireland's involvement in the First World War," she says, "in particular, the experiences of tens of thousands of young men from nationalist backgrounds who fought, came home and then had their difficulties compounded when their communities, the state, turned against them."

Perhaps, the word that best describes her books is "gritty" and she certainly never shies away from difficult subjects, among them, suicide, teen pregnancy, PTSD, death and bereavement and addiction. In this, the "most challenging" historical novel yet, characters face conflict, prejudice, intimidation and actual attacks – but, as the title suggests, there is also a sense of optimism that, a little like the Irish border, a solution to all their woes will yet found.

"There is a fair bit of violence in the book," the CBI (Children's Books Ireland) winner admits, "but it is necessary for the story which puts girls centre stage and has the strongest feminist heart yet. There was this prevailing idea that young girls at the time weren't important, were culturally negligible, frivilous...

"That attitude is being challenged now, of course, but making girls the centre of the story and taking their concerns seriously has always been important to me. I was always a feminist at school and went on women's marches when it wasn't very fashionable to do so, so it's been really interesting to see my readers as the new generation of feminism which is fantastic. I guess I have always been interested in the experiences of people who don't fit neatly into boxes."

Until recently a confirmed bachelorette, she sees herself as a prime example. "I'm 51 and I spent whole adult life single until I fell in love with an old friend with whom I used to run a folk club," the author reveals. "We've been together for just under a year and that's been a massive change in my life. For all those years, I was aware of how society was organised around couples and how life isn't like that for everyone, so I guess I have always been interested in people who haven't taken the most obvious path."

Friends, she says, have likened parts of protagonist Polly's "flawed" personality to parts of her own "angst-ridden" 15-year-old self – "quite feisty, confused, hot-headed and impetuous", but now, having entered her 50s, the writer has mellowed somewhat, even if she still has a quick retort when challenged on the doorsteps.

"I have been on doorsteps, canvassing for the Alliance party, and I get quite a positive response now," Wilkinson reports, "but I remember someone saying to me – just before he slammed the door in may face – that I couldn't 'sit on the fence'. I replied that that was the whole point – there doesn't have to be a fence.

"There are no 'messages' in my books, as such, but I would like readers, whatever their age, to identify with the characters and empathise with the kind of struggles they had, to have conversations around identity and to maybe just be reminded of how horrible that time was in Northern Ireland.

"Is there hope at the end? Yes, there's always hope, but that hope is tempered by the fact readers know the future here is problematic and the things they were fighting over in 1921 have still not been resolved. Northern Ireland is a much more complex place than it has been given credit for; the story isn't just black and white – or rather, it isn't just orange and green."

:: Hope against Hope (Little Island) is published on March 5.