TALK about a coincidence. Just before I left the office to go and meet Declan O’Rourke for a chat about his new album, Chronicles Of The Great Irish Famine, I lifted the Belfast News Letter and was shocked by the front page headline: “Potato farmers left facing ‘catastrophe” it read.

One hundred and seventy two years after the Great Hunger hit Ireland – all parts of it, by the way – we are still having problems growing potatoes. The big difference is that no-one is going to starve in 2017 because of a lack of potatoes and no government would be seen to be moving food away from a place where starvation was rampant and people were dying by the roadside.

The Irish we are today is a product of that cataclysmic event as, in the words of Brendan Mac Suibhne in his book The End of Outrage, after the Famine, Irish people “exchanged themselves for the future” and those who survived the holocaust moved away, culturally, linguisticly, geographicaly, from their pre-Famine lives.

“To remember everything is a form of madness” says Hugh in Brian Friel’s play Translations and to avoid going mad, the Irish of the second half of the 19th century understandably chose to forget and to forge a new life for themselves.

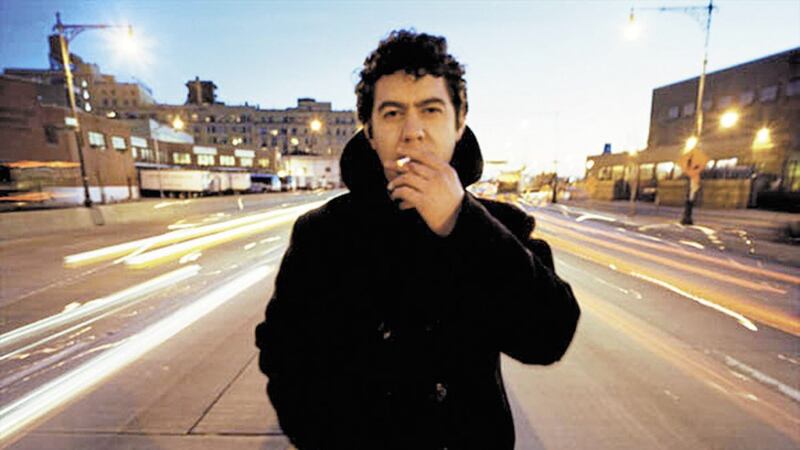

Singer-songwriter Declan O’Rourke fell into the well of this wilful forgetfulness when he chanced upon a book about workhouses and discovered a family connection.

“I was very, very lucky with the first book I picked up and it was completely accidental,” the Dubliner told me over a Coke and a coffee (rock and roll).

“I’d known that my grandfather had been born in a workhouse but I had no idea what that meant so I decided to find out. But I shelved the idea for a few months until one day I was passing through Eason’s in Dublin and, in the bargain section, I came across a book called The Workhouses of Ireland by John O’Connor, a Kerryman, and I thought ‘well, here’s my answer’ and I had no idea it was connected to the Famine.

“And then I opened the first page and the second paragraph down, O’Connor writes, 'The man, who carried his wife from the workhouse to their old home, mile after weary mile, and was found next morning dead, his wife’s feet held to his breast as if he was trying to warm them…’

“That is probably the most powerful thing I have ever read,” says O'Rourke and indeed the quote changed the course of his artistic career.

He wrote a song called Poor Boy’s Shoes – which became one of his most requested even though he had never recorded it – based on the story by O’Connor who in turn got it from Peadar Ó Laoghaire’s book Mo Scéal Féin. The family in question were called Buckley.

O'Rourke started to read voraciously about the Famine but he found that stories like the one above are few and far between. Most books deal with the dry material of legislation, statistics, analysis and so on – perhaps because, as mentioned, people have chosen to forget and so the human stories have died out or weren’t reported or weren’t talked about at the time.

What O'Rourke has chosen to do in Chronicles Of The Great Irish Famine is to take those personal stories and to share them in the best way he knows how, through music and song.

The 13 tracks add human emotion to the stories behind what, for most of us, is a fog of half-formed perceptions. We’ve seen the lithographs of the starving populace but O'Rourke’s songs add a level of compassion and empathy – though that isn’t to say there isn’t anger there as well.

“I tried to find the most illustrative stories that would give an overview of what was happening at the time. Those lithographs tend to push it into the distant two-dimensional past and you can’t communicate with that.

“You get much more emotional depth in a song and you put your own people into the story and that’s how you empathise with others. Empathy comes when you can imagine it happening to you or when you think ‘That could have been my mother or father’ and so on. I think that art helps us to do that,” he says.

Of course, it depends whose shoes you chose to put yourself into. One song that hit me like a hammer is called The Villain Curry Shaw, which tells the tale of a brig called the Hannah which left Warrenpoint in 1849 to make its way with its human cargo to Canada. On April 29, the ship got stuck in ice. All would be saved if due procedure was followed; however, the captin of the vessel, Curry Shaw, had the hatch nailed down, condemning all on board to an icy death as he and one other crew member prepared to make good their escape.

Luckily, another crew member countermanded the order and, as the song describes: A frantic race began among the crew and men/To lower people down on to the ice floes as she leant/Some refused to leave, terrified with fear/They were swallowed in that dreadful hour the Hannah disappeared.

One hundred and twenty eight people survived and the rest of the story is told on the album’s sleeve notes – indeed the historical context of all the stories on the album are to be found in the notes, making the album even more invaluable.

But why should we remember such an event, catastrophic though it was, at this moment in time?

“Well, I think the most important thing I’ve been trying to get across about the whole project is that with all the sh*t that’s happening in the world at the minute – we are on the brink of a huge famine in Yemen, there is terrible stuff going on in Syria and Myanmar – there will always be disaster and catastrophe but sometimes it is preventable,” he says.

Knowing and feeling what the Famine Irish went through via songs like Laissez Faire, where a mother cannot feed her infant son (“All the good I have in my body is gone”) while “… everything that’s worth ‘ating in the country/Is shifted off to England by the Queen’s navy/Y’er man Trevalyan says is ‘Laissez Faire” will hopefully elevate us up to having the same affinity for a starving Yemeni mother who is suffering a similar fate in this 21st century.

:: Declan O'Rourke is playing at The Glassworks in Derry next Wednesday, December 20, at 8pm. You can get Chronicles Of The Great Irish Famine at declanorourke.com