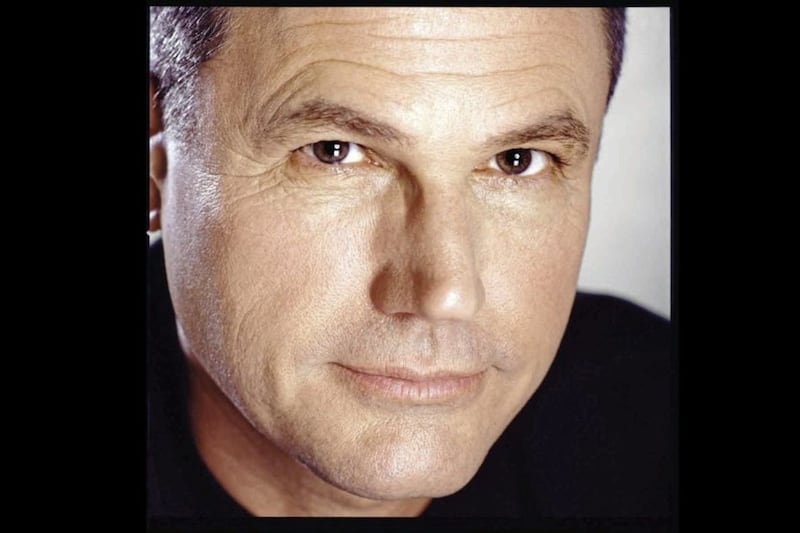

SURVIVAL in the face of catastrophe is something which continues to fascinate Belfast film-maker Terry George, whose latest movie The Promise sheds new light on “the great unknown catastrophe of the 20th century”.

The film is set against the background of what many historians view as an undeniable act of genocide by the forerunner to the Turkish state, which resulted in the massacre and deportation of 1.5 million mostly Christian Armenians between 1915 and 1917.

On general release from tomorrow, George says The Promise is: “An epic love story told against the backdrop of what happened to the Armenians towards the end of the Ottoman empire in 1915.

“It’s a love triangle caught up in the midst of a big political drama, very much in the genre of David Lean’s great movies like Dr Zhivago, or Ryan’s Daughter or Warren Beatty’s Reds.”

Christian Bale (Empire Of The Sun, American Hustle, The Dark Knight) and Oscar Issac (Ex Machina, A Most Violent Year) star as love rivals, alongside French-Canadian actress Charlotte Le Bon, who appeared in last year’s Anthropoid with Jamie Dornan and Cillian Murphy.

"Charlotte's character and Oscar Issac's character are both Armenians, while Christian Bale's character is an American reporter covering the outbreak of war," says George, setting the historical context for the movie he directed and co-wrote with Robin Swicord.

“From the 15th century on, the Ottoman empire dominated most of southern Europe right down to Persia. As that empire began to crumble at the turn of the 20th century, the leaders decided they needed to cleanse the empire of what they considered traitorous communities – the Armenians, the Greeks, the Syrians – who were mostly Christians.

“When war broke out, they used that conflict as an excuse to basically move the Armenians, to drive them out of their villages and homeland and slaughter them.

“The main technique was to drive them into the desert, saying that they were moving them south away from the war zone, but in fact they just forced hundreds and thousands of them into death marches.”

The impact of living in a place of conflict is something which the west Belfast man has explored before, in his earlier Oscar-nominated films In the Name of the Father about the Guildford Four, and Hotel Rwanda about the genocide of the Tutsi people by the ruling Hutu.

However, it was the short film The Shore, shot over six days on the shores of Killough near his family home, that finally won him an Oscar in 2012.

The Promise has divided international opinion, just as the horrific event it depicts continues to do so to this day.

Some criticism has labelled it propaganda, as it was financed by the late Armenian-American businessman and philanthropist, Kirk Kerkorian. George rejects the claims, arguing that, like all of his films, it was fastidiously historically researched.

“It’s like climate change; it’s one-sided because it’s been proven. We say, here are the facts, here’s what most historians say and it’s recognised around the world except by governments where the Turkish strategic power decide to manipulate it.

“While people go on and say it’s denied, it’s just a tactic to divert away from the horror of the thing and [the fact that] that no-one was ever held accountable.”

He adds: “The Armenian genocide was the great unknown catastrophe of the 20th century. It has been denied and suppressed by successive Turkish governments. It’s actually how the word genocide was actually coined.

?“Because of the way it had disappeared from history, Hitler used that almost as an excuse for his generals as he was ordering them into war, saying, ‘Who after all remembers the Armenians?’”

“The producers wanted the story to be told in a way and I agreed with that. The fact that it has got such a joyous reception by the Armenian people as their story has finally been told is also fine by me.”

?The film has received a mixed critical reaction, although it gained a 96 per cent audience rating on movie review website Rotten Tomatoes.

While the film-makers haven’t had any direct contact from the Turkish government, George says: “There’s been letters written and threats made to some people and a lot of negative voting on the internet and stuff like that.”

He told the Irish Independent recently that it was screened twice at the Toronto Film Festival to a total audience of 3,000. By the end of that week, it had received 86,000 reviews on IMDb, 55,000 giving a score of one out of 10 and 30,000 giving 10 out of 10.

George has had personal experience of living in conflict; in 1975, at age 23, he was sentenced to six years imprisonment in Long Kesh after becoming caught up in republican paramilitary activity.

Released in 1978, he and his family moved to New York three years later where he had the opportunity to develop his writing talent, first as a playwright, then later as a screenwriter.

Perhaps a film should be made of the personal catastrophe of his own remarkable journey that led to where he is today?

“Well, I won’t be writing it,” he laughs. “I wouldn’t put it [his imprisonment] as catastrophic on the level of some of the events I’ve portrayed, but life and what you experience in your earlier years informs your outlook on certain things.

“For me growing up in Belfast gave me more of an insight into how ordinary people managed to deal with what catastrophes that befell them, whether it would be Giuseppe Conlon, or the mothers of the hunger strikers, or whatever.

“That’s what interested me the most and I found that vehicle telling stories and having an audience empathise with your lead characters.”

He’s currently working on expanding The Shore into a full-length feature which will deal with the impact of exile.

“What interests me is finding great human stories of survival whatever that might be. Clearly I’m interested in educating people through cinema and if the right opportunity arises, sure, I don’t rule anything out.”

:: The Promise is in cinemas from tomorrow.