FOR 100 years objects left behind from the Easter Rising have borne silent witness to this seminal event in modern Irish history and in his new book Dublin historian John Gibney has delved deep into the archives to unearth artefacts and documents that shed light on aspects of its origins, course and outcome.

A History of the Easter Rising in 50 Objects explores the stories attached to these objects in a thought-provoking way, going beyond analysing the Rising's political significance and getting to the heart of the people associated with them, who were directly and indirectly involved.

Currently Glasnevin Trust Assistant Professor in Public History and Cultural Heritage at Trinity College Dublin, Gibney also brings a cultural viewpoint to the events of the Rising by looking at literature, drama and sport.

"OK nobody was playing hurling in O'Connell Street during the midst of the rioting but the cultural nationalism of the Gaelic League and GAA did shape the attitudes of the people who fought in the rising and some of the leaders certainly were involved in cultural activities," says Gibney referring to his inclusion in the book of Sean MacDiarmada's hurley.

One of the seven leaders of the 1916 Rising, MacDiarmada was one of many young nationalists attracted by the GAA in the early 20th century and who later fostered support for political independence among its members. Born near Kiltyclogher in Co Leitrum, it was while working in Belfast that MacDiarmada joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in 1906.

While acknowledging the need to include in his book the Proclamation of Independence and the Ulster Covenant "because you couldn't have had the Easter Rising without the Irish Volunteers and you couldn't have had them without the Ulster Volunteer Force", Gibney was open in his research to what history would unveil to him.

To his delight, his searches of the archives of Kilmainham Gaol Museum, the National Museum of Ireland and lesser known libraries like The Allen Library unveiled some hidden gems.

"Stuff came out the woodwork such as the platter that Roger Casement used during his appeal against his conviction for treason which was at a Gaelscoil in Tralee, a baton used in the Howth gun-running and rubble and cartridges from the GPO," he says.

Many of his discoveries, including Sean MacDiarmada's hurley and biscuits given to suffragette and labour nationalist Kathleen Lynn in prison, were not on public display – rather hiding in a cupboard in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin.

One of his favourite finds was a 1916 Memorial Card bought in 17 Moore Street in 1917, the same building from which 11 months previously James Connolly had been carried out badly wounded and next door to the building in which the leaders of the Rising apparently made the final decision to surrender.

"When I turned it over I discovered an inscription from the the guy that bought it, who was in the Irish Volunteers himself. He told how after the Rising he was almost arrested by the British army but the soldier who was trying to arrest him turned out to be his cousin and he let him off the hook."

While James Connolly's bloodstained shirt and hunger striker Thomas Ashe's handcuffs certainly make for striking images of men remembered as heroes of the Irish revolution, Gibney believes that the cricket bat stolen from the window of sporting goods store JW Elvery and Co on Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street) is the most significant artefact in his book.

Known as 'the cricket bat that died for Ireland', it was 'killed' by a British .303 round that is still lodged in in, probably fired in the early days of Easter Week, before the centre of Dublin became an inferno.

"While only a relatively small amount of people took part in the Easter Rising, a huge amount of people were affected by it; they witnessed it and their lives got torn upside down by it. The cricket bat symbolises that the impact of the Easter Rising spread to a much wider amount of people than those that fought at the GPO and the other garrisons," says Gibney.

Sackville Street was one of Dublin's commercial heartlands and the opportunity for looting was soon realised as "poverty took precedence over politics". Children featured prominently in this looting and Gibney poignantly recalls "one of the first shops to be looted was Noblett's sweet shop".

In his book Gibney portrays the human aspects of the political violence, saying "the cost of fighting extended, as always, far beyond those who actually fought". One such example was five-year-old James Gibney who died three weeks after the Rising. The cause of death was listed as 'probably heart disease and shock. No inquest unnecessary.'

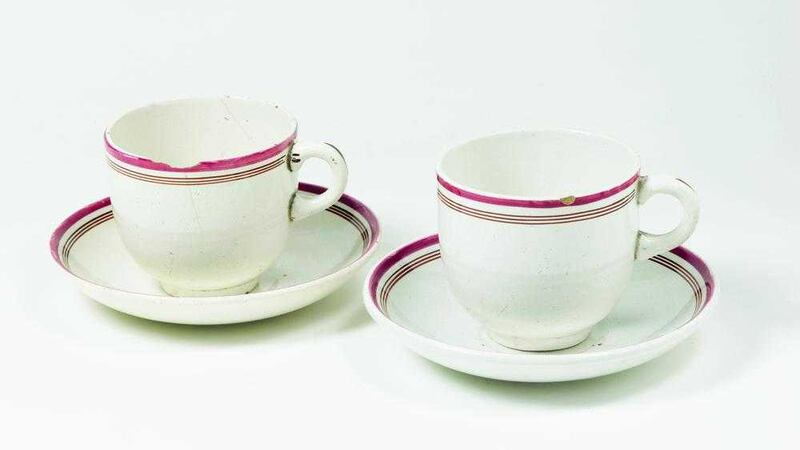

In another artefact, teacups and saucers used by Patrick and Willie Pearse at the last family meal they had before going out to take part in the Easter Rising symbolise "a humble link to ordinary life before the upheavel of April 1916" and a reminder to his family of their lost followed their execution.

As with most periods of history, Gibney discovers some gaps of information and some unreliable documents – none more so than the newspapers that fed into the rumour mill that was rife in Dublin at the time.

"There were reports that German U-boats were seen sailing into Dublin Bay and one of the artefacts I found was an American newspaper printed on Easter Tuesday which reported that the GPO had been recaptured by the British. It was all nonsense."

Civilian testimonies filled in some of these gaps. Gibney includes an account from Limerick accountant Wesley Hanna, who arrived by train for his work on Tuesday April 25 to find the station and city occupied by the military.

The Easter Rising and its aftermath became the catalyst for the independence movement that arose in Ireland in the years that followed.

"Even without an Easter Rising you would still have had the British threatening to mobilise conscription and you would have had people hostile to that. But the independence movement that arose was basically one that was defined by the Easter Rising and the British heavy-handedness, executions and mass internment that followed it.

"The hardcore of what became the IRA was forged by not just the veterans of the Easter Rising but those people who had no connection with it who were then being detained with like-minded people in prison camps like Frongoch in Wales."

In this the centenary year of the Easter Rising, Gibney believes the events of April 2016 "is the history of everyone on the island whether they disagree with it or not".

"Politicans and whoever can make whatever polemic points they want about it but the historian in me thinks that if people are learning about it and debating it that can only be good and hopefully my book will help do this," he adds.

:: A History of the Rising Rising in 50 Objects by John Gibney is published by Mercier Press, available now.